Overview

Querying in GraphQL is just one part of the equation. We've seen the power of specific and expressive queries that let us retrieve exactly the data we're looking for, all at once.

But when we want to actually change, insert, or delete data, we need to reach for a new tool: GraphQL mutations.

In this lesson, we will:

- Boost our schema with the ability to change data

- Explore mutation syntax

- Learn about GraphQL

inputtypes - Learn about mutation response best practices

- Create a Java record to hold immutable response data

Mutations in Airlock

Onward to the next feature in our Airlock API: creating a new listing.

Our REST API comes equipped with an endpoint that allows us to create new listings: POST /listings.

This method accepts a listing property on our request body. It should contain all of the properties relevant to the listing, including its amenities. Once the listing has been created in the database, this endpoint returns the newly-created listing to us.

All right, now how do we enable this functionality in GraphQL?

Designing Mutations

Much like the Query type, the Mutation type serves as an entry point to our schema. It follows the same syntax as the schema definition language, or SDL, that we've been using so far.

We declare the Mutation type using the type keyword, then the name Mutation. Inside the curly braces, we have our entry points, the fields we'll be using to mutate our data.

Let's open up schema.graphqls and add a new Mutation type.

type Mutation {}

For the fields of the Mutation, we recommend starting with a verb that describes the specific action of our update operation (such as add, delete, or create), followed by whatever data the mutation acts on.

We'll explore how we can create a new listing, so we'll call this mutation createListing.

type Mutation {"Creates a new listing"createListing: #TODO}

For the return type of the createListing mutation, we could return the Listing type; it's the object type we want the mutation to act upon. However, we recommend following a consistent Response type for mutation responses. Let's see what this looks like in a new type.

Note: In this course, we've defined all of our types in a single schema.graphqls file. This isn't required, however; the DGS framework builds the final GraphQL schema from all .graphqls files it finds in the schema folder. This means that as your schema grows larger, you can choose to break it up across multiple files if preferred.

The Mutation response type

Return types for Mutation fields usually start with the name of the mutation, followed by Payload or Response. Don't forget that type names should be formatted in PascalCase!

Following convention, we'll name our type CreateListingResponse.

type CreateListingResponse {}

We should return the object type that we're mutating (Listing, in our case), so that clients have access to the updated object.

type CreateListingResponse {listing: Listing}

Note: Though our mutation acts upon a single Listing object, it's also possible for a mutation to change and return multiple objects at once.

Notice that the listing field returns a Listing type that can be null, because our mutation might fail.

To account for any partial errors that might occur and return helpful information to the client, there are a few additional fields we can include in a response type.

code: anIntthat refers to the status of the response, similar to an HTTP status code.success: aBooleanflag that indicates whether all the updates the mutation was responsible for succeeded.message: aStringto display information about the result of the mutation on the client side. This is particularly useful if the mutation was only partially successful and a generic error message can't tell the whole story.

Let's also add comments for each of these fields so that it makes our GraphQL API documentation more useful.

type CreateListingResponse {"Similar to HTTP status code, represents the status of the mutation"code: Int!"Indicates whether the mutation was successful"success: Boolean!"Human-readable message for the UI"message: String!"The newly created listing"listing: Listing}

Lastly, we can set the return type of our mutation to this new CreateListingResponse type, and make it non-nullable. Here's what the createListing mutation should look like now:

type Mutation {"Creates a new listing"createListing: CreateListingResponse!}

The Mutation input

To create a new listing, our mutation needs to receive some input.

Let's think about the kind of input this createListing mutation would expect. We need all of the details about the listing itself, such as title, costPerNight, numOfBeds, amenities and so on.

We've used a GraphQL argument before in the Query.listing field: we passed in a single argument called id.

type Query {listing(id: ID!): Listing}

But createListing takes more than one argument. One way we could tackle this is to add each argument, one-by-one, to our createListing mutation. But this approach can become unwieldy and hard to understand. Instead, it's a good practice to use GraphQL input types as arguments for a field.

Exploring the input type

The input type in a GraphQL schema is a special object type that groups a set of arguments together, and can then be used as an argument to another field. Using input types helps us group and understand arguments, especially for mutations.

To define an input type, use the input keyword followed by the name and curly braces ({}). Inside the curly braces, we list the fields and types as usual. Note that fields of an input type can be only a scalar, an enum, or another input type.

input CreateListingInput {}

Next, we'll add properties. To flesh out the listing we're about to create, let's send all the relevant details. We'll need: title, description, numOfBeds, costPerNight, and closedForBookings.

input CreateListingInput {"The listing's title"title: String!"The listing's description"description: String!"The number of beds available"numOfBeds: Int!"The cost per night"costPerNight: Float!"Indicates whether listing is closed for bookings (on hiatus)"closedForBookings: Boolean}

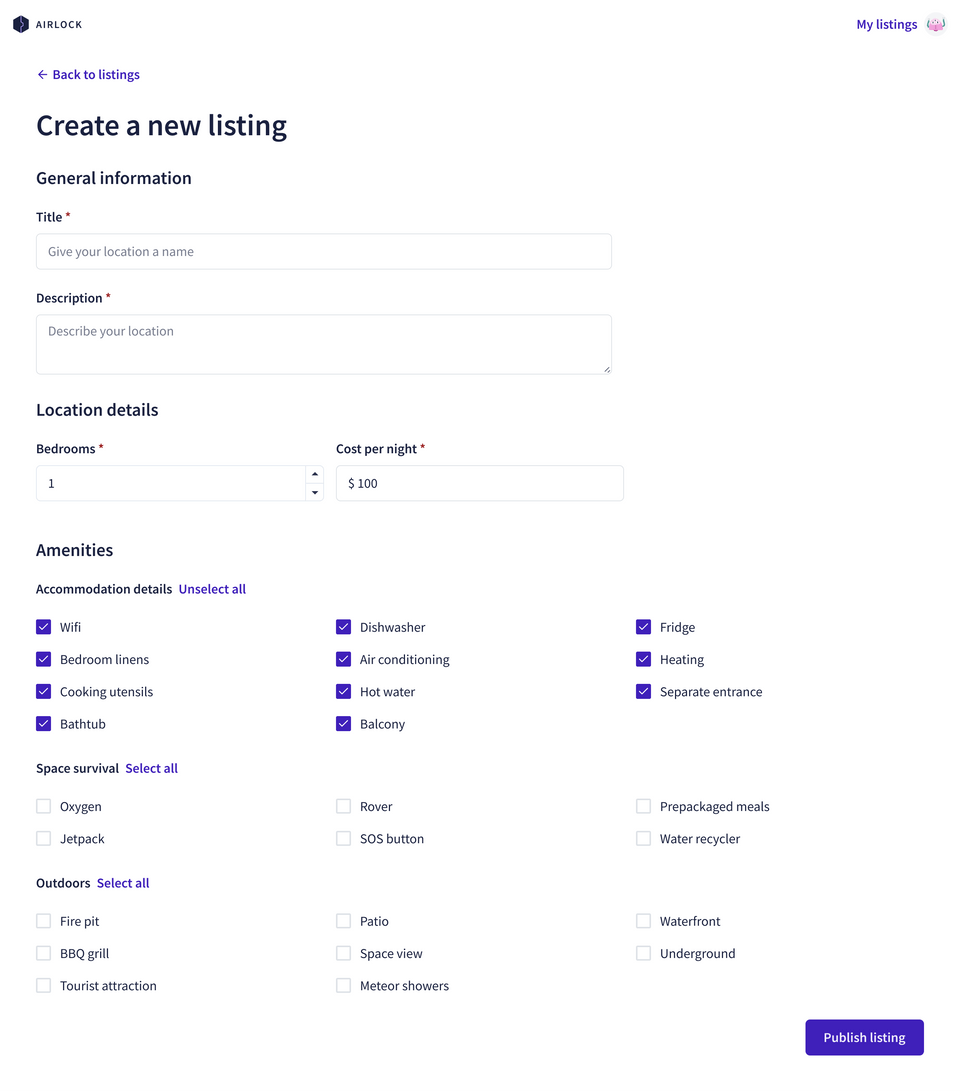

We also need to specify the amenities our listing has to offer. Notice that the amenity options in our mock-up for creating a new listing are pre-defined; we can only select from existing options. Behind the scenes, each of these amenities has a unique ID identifier. For this reason, we'll add an amenityIds field to CreateListingInput with a type of [ID!]!.

input CreateListingInput {"The listing's title"title: String!"The listing's description"description: String!"The number of beds available"numOfBeds: Int!"The cost per night"costPerNight: Float!"Indicates whether listing is closed for bookings (on hiatus)"closedForBookings: Boolean"The Listing's amenities"amenities: [ID!]!}

Note: You can learn more about the input type, as well as other GraphQL types and features in Side Quest: Intermediate Schema Design.

Using the input

To use an input type in the schema, we can set it as the type of a field argument. For example, we can update the createListing mutation to use CreateListingInput type like so:

type Mutation {"Creates a new listing"createListing(input: CreateListingInput!): CreateListingResponse!}

Notice that the CreateListingInput is non-nullable. To run this mutation, we actually need to require some input!

Building the ListingService method

As we've done for other requests, we'll build a method to manage this REST API call to create a new listing.

Back in datasources/ListingService, let's add a new method for this mutation.

public void createListingRequest() {return client.post()}

This time, because the endpoint uses the POST method, we'll chain .post() rather than .get().

Next, we'll craft our destination endpoint in-line. We'll specify a uri of /listings, but before calling .retrieve(), we'll first call .body() to specify our request body.

public void createListingRequest() {return client.post().uri("/listings").body()}

We'll talk about what we pass in for the request body in just a moment, but for now let's finish the method.

It accepts a listing argument of type CreateListingInput, so let's start by importing this at the top of the file.

import com.example.listings.generated.types.CreateListingInput;

Note: If you don't see a valid import for the generated CreateListingInput type, try stopping and restarting the server.

Next, we'll give our method a return type of ListingModel, and include the CreateListingInput parameter called listing.

public ListingModel createListingRequest(CreateListingInput listing) {// ...method body}

To complete the syntax of our call to the /listings endpoint, we'll chain on the retrieve and body methods. Finally, to convert the response to an instance of ListingModel, we'll pass ListingModel.class to the final body() method call.

public ListingModel createListingRequest(CreateListingInput listing) {return client.post().uri("/listings").body() // TODO!.retrieve().body(ListingModel.class);}

Now we can return to the question of how we'll send our request data to the endpoint—in other words, what we need to pass to that first body() method!

Defining a CreateListingModel record

When creating a new listing via the POST /listings endpoint, we have a couple of requirements to keep in mind.

- We know that this endpoint looks for a

listingproperty on the request body. - To send data as part of our request, we can't use a regular Java class; we'll need to serialize it to be sent as part of our HTTP request.

Let's think about the first requirement. Our method receives a CreateListingInput type, with all the details about the listing to be created; this means that it has all the necessary information for posting to the /listings endpoint, but we need all of that data to be contained in a property called listing on our request body.

We could create a new class, give it a listing property, and set up a setter method, as shown below.

public class CreateListing {CreateListingInput listing;public void setListing(CreateListingInput listing) {this.listing = listing;}}

But that's a little bit more boilerplate than we need; after all, we really just want to set a listing property once, use it as part of our request body, and not change it again. This means we can save ourselves some time and code, and use a Java record instead!

In the models directory, create a new file called CreateListingModel.

📂 com.example.listings┣ 📂 datafetchers┣ 📂 models┃ ┣ 📄 CreateListingModel┃ ┗ 📄 ListingModel┣ 📄 ListingsApplication┣ 📄 WebConfiguration

By default, your IDE might give you some class-based boilerplate, but let's right away update our class to be a record instead.

package com.example.listings.models;public record CreateListingModel() { }

To set up our record with a listing property of type CreateListingInput, all we need to do is pass our property and type into the parentheses after the record's name. (And don't forget to import CreateListingInput!)

import com.example.listings.generated.types.CreateListingInput;public record CreateListingModel(CreateListingInput listing) { }

Now we have the ability to create new records on the fly—we can pass them a CreateListingInput, and they'll automatically take care of creating a listing property to hold the data.

Let's return to our ListingService method and make use of this new record. At the top of the file, import CreateListingModel.

import com.example.listings.models.CreateListingModel;

Then down in our createListingRequest method, just before the POST request, we'll create a CreateListingModel record and pass in the listing that our method receives.

public ListingModel createListingRequest(CreateListingInput listing) {new CreateListingModel(listing);// "/listings" post request}

Now, we can think about our second requirement. In order to send the contents of our new record along with our request as its body, we need to serialize it first. Serialization prepares a Java class or record to be included as part of an HTTP request.

Serializing our listing input

We've used Jackson's ObjectMapper to convert JSON objects into Java classes; now we need to go from Java classes to JSON objects. Spring gives us a utility called MappingJacksonValue to achieve this.

At the top of the file, import MappingJacksonValue from Spring Framework.

import org.springframework.http.converter.json.MappingJacksonValue;

Down in the createListingRequest method, we'll create a new instance of MappingJacksonValue, passing our record into it. We'll call the result serializedListing.

MappingJacksonValue serializedListing = new MappingJacksonValue(new CreateListingModel(listing));

Alright—last step for this method! We'll pass this serializedListing in as our POST request's body.

public ListingModel createListingRequest(CreateListingInput listing) {MappingJacksonValue serializedListing = new MappingJacksonValue(new CreateListingModel(listing));return client.post().uri("/listings").body(serializedListing).retrieve().body(ListingModel.class);

That's it for the call to the endpoint—time to use it in our datafetcher.

Practice

CreateListingResponse), why is the modified object's return type (Listing) nullable?input type in our schema?Key takeaways

- Mutations are write operations used to modify data.

- Naming mutations usually starts with a verb that describes the action, such as "add," "delete," or "create."

- It's a common convention to create a consistent response type for mutation responses.

- Mutations in GraphQL often require multiple arguments to perform actions. To group arguments together, we use a GraphQL input type for clarity and maintainability.

Up next

In the final lesson, we'll connect the dots to make our mutation operation fully-functional—and create some new listings!

Share your questions and comments about this lesson

This course is currently in

You'll need a GitHub account to post below. Don't have one? Post in our Odyssey forum instead.